As discussed in depth in ‘How to Develop Musicality – Focusing on the How of Drumming with Parameters‘, it’s not what we play that makes things sound great, it’s how we play them.

This is the main reason why we know when a drummer, a beat or a song grooves hard, but we can’t easily tell what it is exactly that makes it groove.

In this lesson we are going to add clarity to this subject.

To briefly recap, the ‘how‘ lies in the way we play multiple layers of variations that can be added on top of the mere data (the ‘what’) of our execution.

While the what is, for example, a sixteenth note beat, the how involves things like dynamics, orchestrations, speed, Hi-Hat articulations, beat placement, micro rhythms, and even swing levels. Things which are often impossible to write down using standard music notation (another reason why they are hard to identify).

I like to call these elements parameters, because of the countless ways we can tweak and combine them. They are the how, and they are the foundation that makes the infinite subtleties and tiny variations that create, define and encapsulate groove possible.

Here is where things get really interesting: creating combinations between these variables generates actual recipes, in which every parameter is an ingredient, and that can be thought of as Groove Formulas.

If we want to understand groove, besides spending time practicing each parameter (which can be done by checking out the dedicated lessons), it’s important to start recognizing these formulas and combinations, the way they sound and the way they affect feel and groove in the music we listen to.

The goal is to use active listening to become aware of the interactions, the variables and the nuances, so that we can learn to easily figure out where groove comes from, demystify it, and then be able to apply the acquired knowledge to our beats and rhythms.

We are going to analyze 12 great examples, in different styles, and we are about to be amazed at the details that emerge once we know what to look for.

Here is a free PDF version of this article:

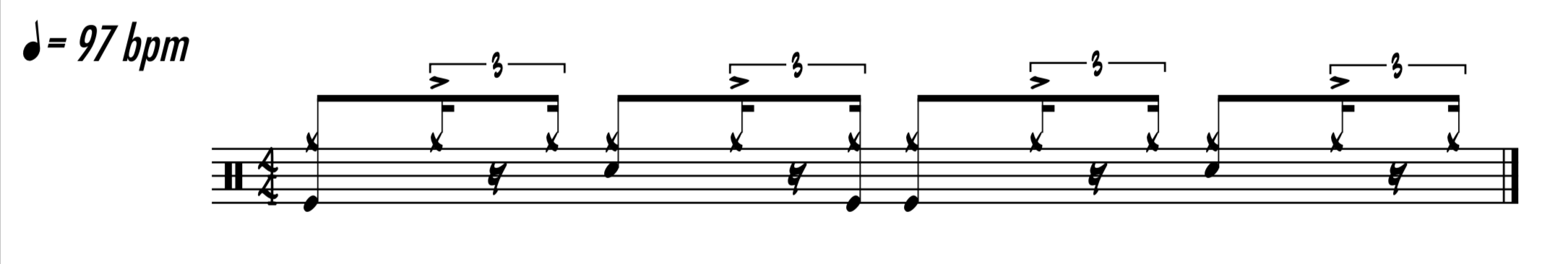

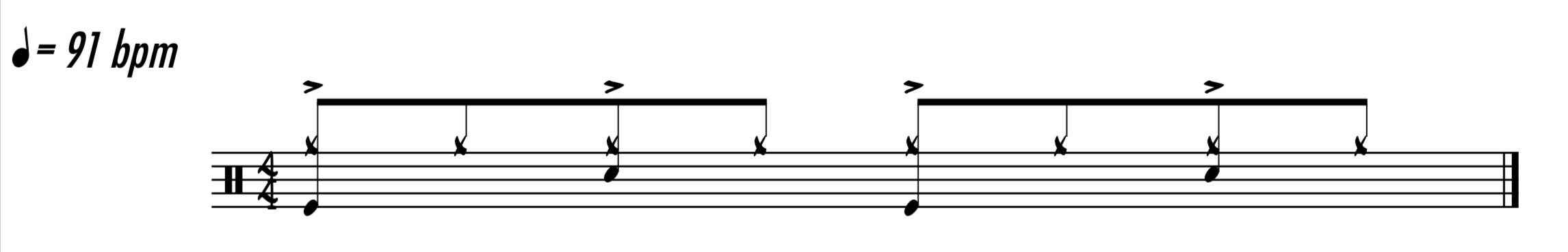

- Pamela (Toto) – Jeff Porcaro

Dynamics: F

Swing level exactly on the sixteenth note triplet.

Hi-Hat slightly open and slightly accented.

Hi-Hat ostinato.

Snare Drum slightly behind the beat.

Let’s listen to Jeff Porcaro’s amazing feel and pocket, and let’s pay attention to the consistency of the slightly delayed Snares, and to the laid back yet powerful groove.

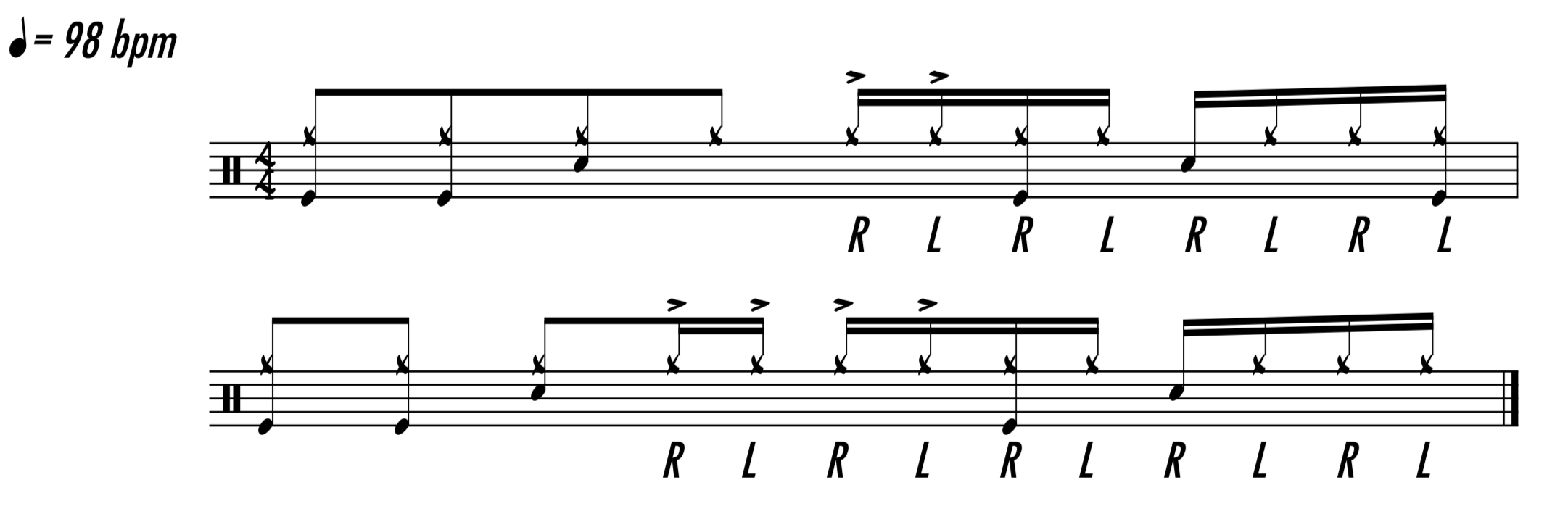

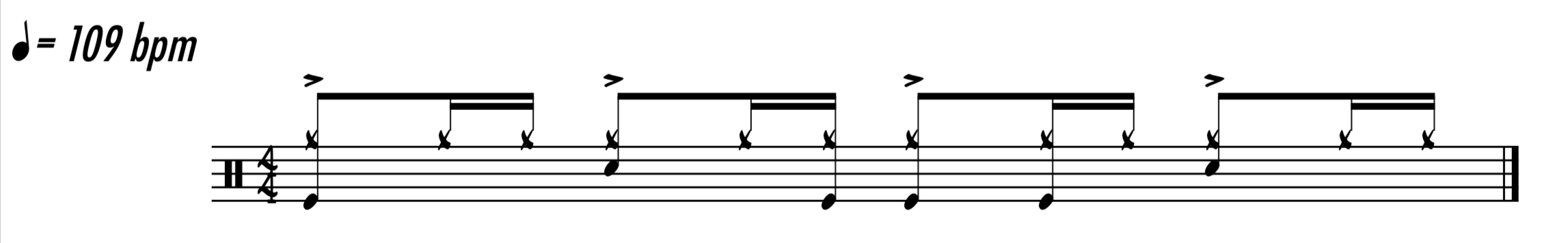

- Human Beings (Seal) – Earl Harvin

Dynamics: MF

In between swing level.

Hi-Hat slightly open and slightly accented.

Everything right on the beat.

This is a classic example of a beat that needs to be examined in order to understand all the nuances and the many layers of parameters involved. Let’s notice the way sixteenth notes are phrased, just barely swung, yet definitely not straight. Also the Hi-Hat plays a few sixteenths, probably overdubbed, which sound like waves of accents, very musical in the way their volume goes up and down. These are part of the details we cannot transcribe. But we can listen to them and try to reproduce them by ear.

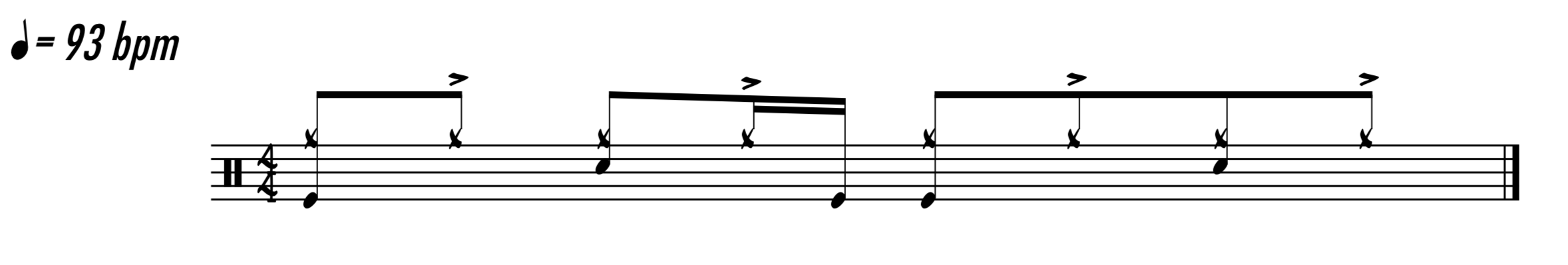

- You Got To Believe (Paulo Mendonca) – Anton Roos

Dynamics: FF

Sixteenths played with a very soft swing feel.

Hi-Hat slightly open and completely accented.

Eighth note upbeat Hi-Hat articulation.

Everything really behind the beat.

This is a great, powerful example of what happens to the feel of a song when the drummer plays behind the beat. Anton Roos is really aware of how to make the most of this technique, and the music benefits tremendously as a result. The rhythm guitar is slightly behind the beat and the drums are placed even further on the backside. We can also notice a very light swing feel in the fills, which accommodates the cadence of the guitar.

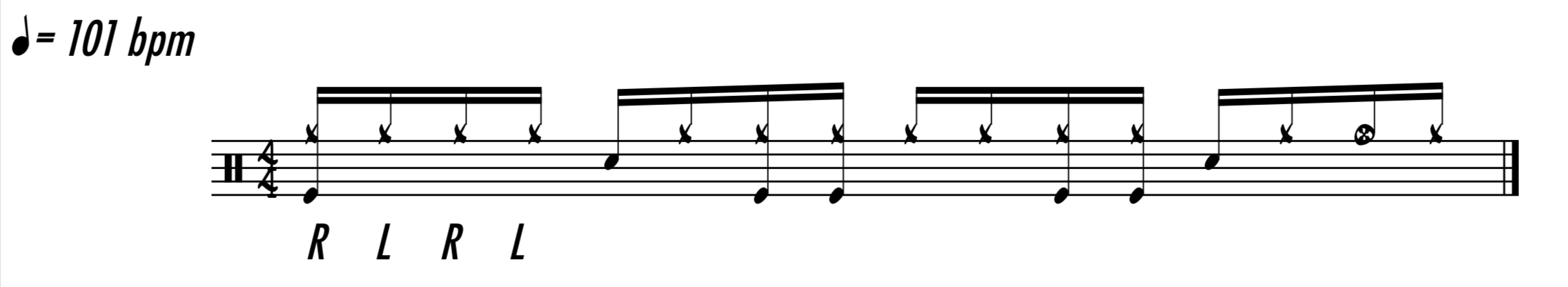

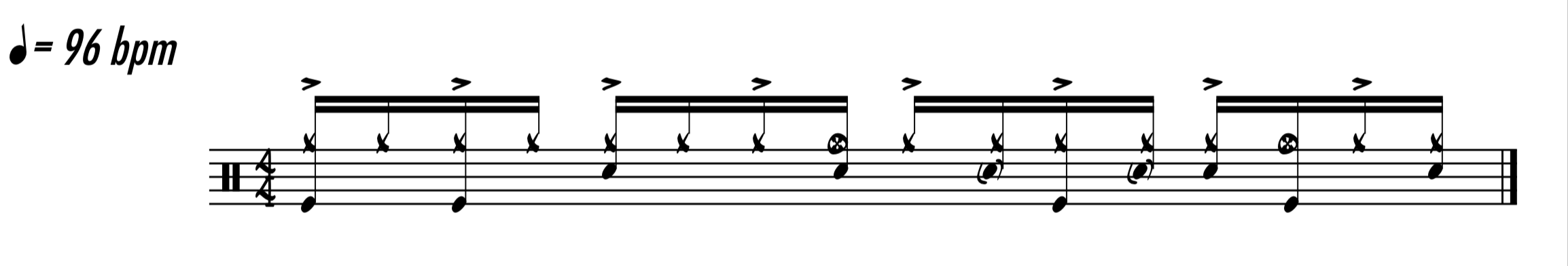

- Belief (John Mayer) – Steve Jordan

Dynamics: F

Sixteenths played with a very loose swing feel.

Hi-Hat closed.

Snare Drum slightly behind the beat.

This is one of my favourite examples when it comes to showing the power of playing sixteenths with a very subtle swing feel. They aren’t quite in between, they are even wider. Yet this small distinction makes all the difference. Steve Jordan is one of the masters of this art. The transcribed groove is the one he plays in the chorus.

- Back In Black (AC/DC) – Phil Rudd

Dynamics: FF Straight eighths.

Hi-Hat slightly open and slightly accented.

Snare Drum really behind the beat.

A very useful exercise is to listen and focus just on the Snare Drum.

We will instantly notice how it is consistently behind, although not always in the same amount (this was recorded before the editing era…), and it will also be apparent how the notes that add more weight to the groove are the ones landing further behind.

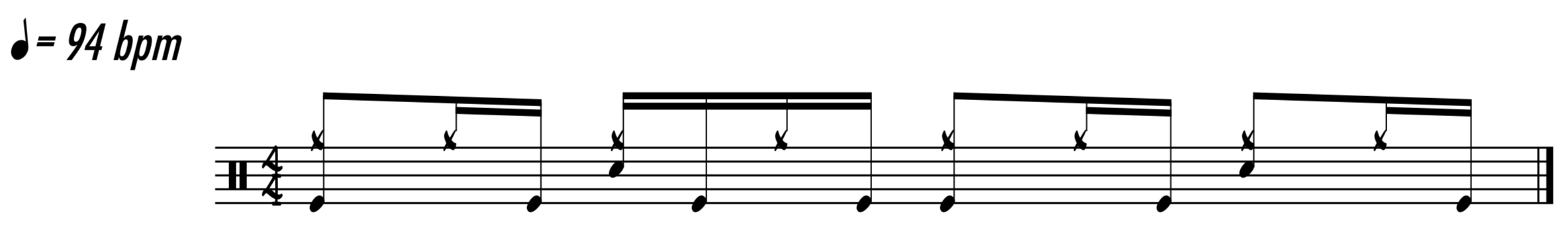

- Break It Down Again (Tears For Fears) – Steve Ferrone

Dynamics: F

Straight sixteenths.

Hi-Hat closed and slightly accented.

Hi-Hat ostinato.

Snare Drum slightly behind the beat.

Steve Ferrone is definitely another drummer who tends to place the Snare Drum slightly behind the beat. Here we have a pretty advanced groove, which even features a Hi-Hat ostinato. The effortlessness with which Steve plays it and the way it drives the song are impressive.

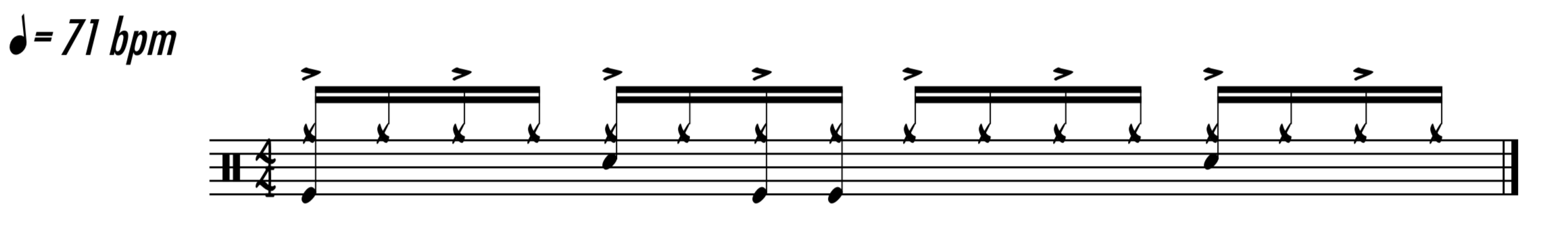

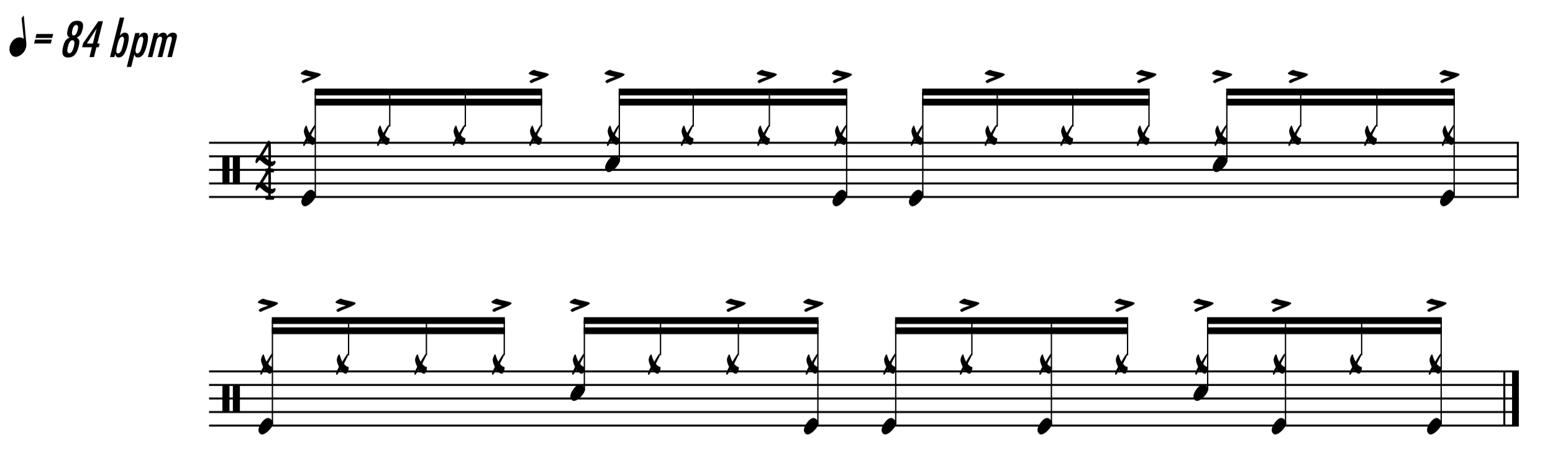

- Badman’s Song (Tears For Fears) – Manu Katchè

Dynamics: F

Straight sixteenths.

Hi-Hat closed and slightly accented.

Everything right on the beat.

Another Tears For Fears piece, this time featuring Manu Katchè on drums. Great pocket drumming in this simple groove, as we can hear in the verse at about 1:30. Consistently on the beat, with no variations, this example is useful to notice that at slow tempos even ‘just’ playing right on the beat generates a really laid back feel.

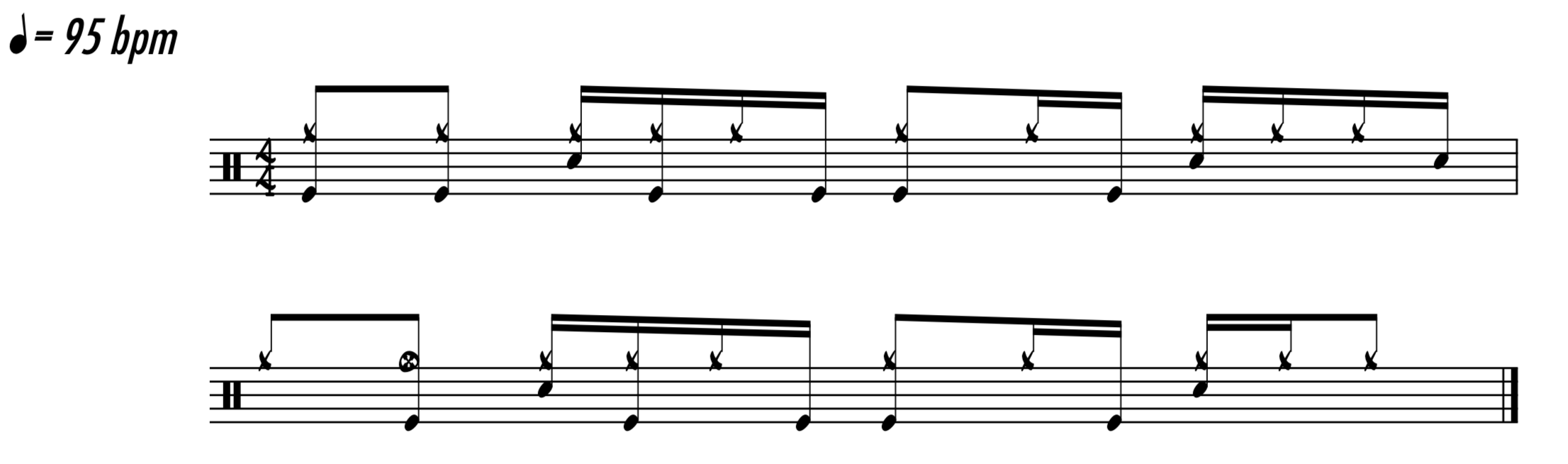

- Ice Pick (Oz Noy) – Keith Carlock

Dynamics: F

Swing level exactly on the sixteenth note triplet.

Hi-Hat closed.

Hi-Hat embellishments in various positions.

Everything right on the beat.

A true groove master, who in this piece gives us a beautiful demonstration of how to use the shuffle feel to add excitement to an arrangement. In some sections the Snare Drum is played slightly behind to add even more weight to the groove, for example in the bridges at 1:40 and 4:00. Keith Carlock adds all kinds of embellishments, Hi-Hat ostinatos and Snare Drum ghost notes to make everything really dense and intense.

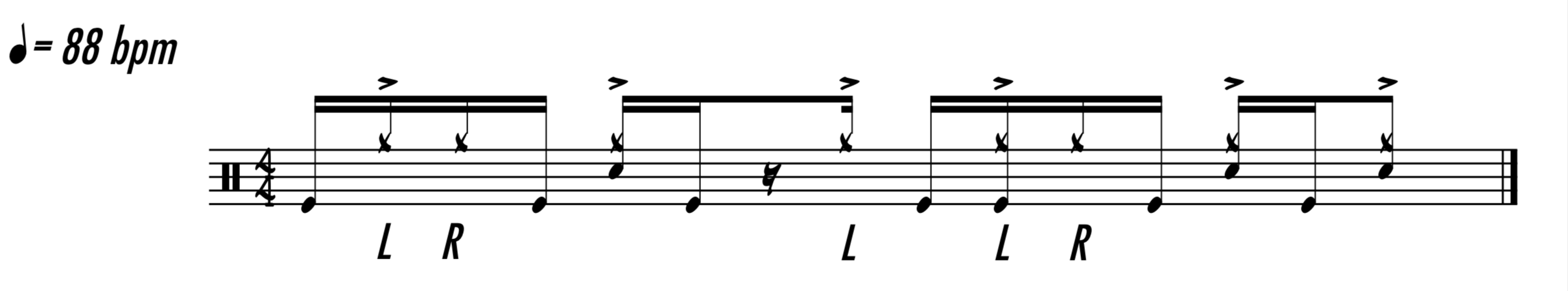

- Funky Drummer (James Brown) – Clyde Stubblefield

Dynamics: MF

Sixteenths played with a very loose swing feel.

Hi-Hat closed and slightly accented.

Snare Drum slightly behind the beat.

A groove that made history, which 50 years after it has been recorded is more fresh, modern and powerful than ever. Again, a great deal of the depth of this beat comes from the barely swung sixteenths. The transcribed measure refers to the legendary break from the middle of the piece, but for 9 minutes Clyde Stubblefield delights us with countless variations.

- Cissy Strut (The Meters) – Zigaboo Modeliste

Dynamics: MF

Sixteenths played with an ‘in between’ swing feel.

Hi-Hat slightly open.

Hi-Hat embellishments in various positions.

Everything slightly behind the beat.

One more of the best beats in the history of drumming. Let’s pay attention to the laid back yet driving pulse achieved by playing on the backside of the beat. Once again part of the magic comes from the in between approach to playing swung sixteenths.

- Fat Cat Song (Slum Village) – Sampled

Dynamics: MF

Sixteenths played with a narrow swing feel.

Hi-Hat closed and unaccented.

Snare Drum slightly behind the beat.

In this example we can hear how a talented producer with a great ear can make even programmed beats sound deep and groovy. This is a tiny sample of the revolutionary J Dilla, whose grooves we are going to examine in a future article.

- Protection (Massive Attack) – Programmed

Dynamics: F

Sixteenths played with a very soft swing feel.

Hi-Hat slightly open.

Hi-Hat embellishments and accents in various positions.

Everything right on the beat.

Let’s wrap this lesson up with this programmed rhythm, from this masterpiece by Massive Attack, in which we can hear the powerful results of using even the slightest amount of swing feel. The effect is amplified by the Hi-Hat embellishments, which include lots of musical accent variations.

It’s inevitable to notice, once again, that the most common formula, that generates the deepest groove, is the one in which the Snare is slightly behind, as we have stressed many times now. Sometimes along with a little swing feel, applied usually to sixteenth notes.

Whenever there is a loose, in between swung cadence, the song has a warm, deep, laid back feel, which is also simultaneously captivating, propulsive and exciting.

This gives us important clues about the direction in which it may be more beneficial to invest our energies.

In order to make the most of this new understanding, here are a couple of suggestions:

- Practice simple grooves and try adding parameters, working first on one at the time (like playing ahead or behind the beat, playing at various dynamics, and so on), then two at the time and then including all of them in different variations simultaneously, like shown for instance on a basic beat in the lesson ‘12 Advanced Ways to Play the Most Basic Drum Beat‘.

- Practice active listening by focusing on these elements, listening to your favourite songs and trying to identify and isolate each parameter, as seen in the above examples, to realize the way that affects the groove.

It’s a lot of fun, and your drumming will benefit tremendously.

Related resources:

‘Groove Mastery & Formulas’ – Altitude Drumming – Volume 8

‘In Session – How To Sound Great On Records’

‘Theory & Concepts’ – Altitude Drumming – Volume 1