As covered in ‘How to Develop Musicality‘, being aware of the layers that contribute to make things sound interesting is the fastest way to become a more musical and, overall, professional sounding drummer.

We can call these elements the ‘how’ of drumming, or, as I like to refer to them because of the way they can be tweaked, ‘parameters’.

Dynamics, tempo, orchestrations, subdivisions, permutations, micro rhythms and time positioning, are some of the most important topics we have explored in this Blog.

Our goal is to take things to the next level by focusing on the details instead of the ‘what’, because we know that’s what makes the difference. Take any beat or idea, and work on these components: it will immediately sound fresh, new, personal and powerfully groovy.

In this lesson we are going to work on one of the most intriguing aspects, the level of swing.

What if instead of just two feels, straight and swung, we could experiment with endless variations? We’ll start by discussing the shuffle feel first and then address the different amounts in which it can be applied, using exercises, grooves and examples that utilize these concepts, to familiarize with each idea in a practical context.

You can download the PDF with the full lesson and all exercises and transcriptions here:

A shuffle rhythm is nothing but a triplet pattern in which the second of the three notes involved is missing. This creates a characteristic swinging cadence which is the foundation of entire musical genres.

Such pulse is called swing feel or shuffle feel.

The first thing that is important to notice is that, since we have two notes in every beat, and since the first one is always on the downbeat, it’s the position of the second note (the upbeat) that makes it a shuffle, simply because it sits closer to the next downbeat than to the previous one.

While in a simple eighth note cadence the upbeat note is exactly in the center of the beat, equally distant from the following and preceding downbeat, in a shuffle it is off-center, and shifted towards the next downbeat.

It’s interesting to notice that in both cases we actually always have just two notes per beat.

It’s the grid on which we place the second note that determines not only the fact that we have a shuffle feel, but also the amount of swing feel that we are going to hear.

Starting from the straight eighths grid, in which upbeats are equally distant from every downbeat, we are going to get a certain amount of swing feel based on how much we move each upbeat note towards the following downbeat.

If we place them exactly on the third eighth note triplet of a triplet grid, we get the typical shuffle feel cadence. However we could go a bit closer to the next downbeat, say on the fourth sixteenth within a sixteenth note grid, thus achieving a narrower swing feel.

On a sixteenth note triplets grid we may place the upbeats on the last sixteenth note triplet: in this case the swing feel will be very hard.

With these three solutions we have basically covered the options allowed by music notation. Yet, we are just scratching the surface of what’s possible to do musically, because the nuances that we can explore are endless.

For instance, if we take the upbeat note and move it from the eighth note triplet closer to the center, the level of swing will be more ‘in the cracks’.

In these cases, we enter the domain of swing levels that are in between eighth notes and triplets. Even just here we have infinite possibilities at our disposal.

This ‘in between’ modality is one of the most interesting and musical variations.

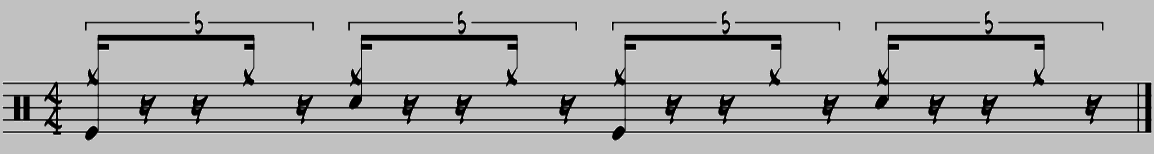

As mentioned above, most of these positions cannot be transcribed, but if we want to get an idea of how they sound we can think of them in quintuplets, like this:

The objective is to learn how to control the amount of swing that we are using, so that we can internalize this technique to the point of applying it to everything we play as another tweakable parameter.

Once we have mastered it we will be able to decide the level of swing we want, and effortlessly use it in rhythms and fills. The results will be amazing in terms of feel, since the amount of swing is one of the essential components that influence it.

Even though there are countless swing levels, and the way in which we can apply them is entirely subjective, we are going to study this parameter by going through 5 amounts, so that we can start working on it within an objective and measurable frame of reference.

In the exercises we are going to name them in the following ways:

As far as eighth note swing feel goes:

- Straight eighths: Straight feel.

- In between eighths: Feeling ‘in between’.

- Eighths perfectly on the triplet: Perfect shuffle/swing feel.

- Narrow eighths (the second note sits on the last sixteenth of a sixteenth note grid): Narrow swing feel (also known and dotted eighth feel).

- Hard eighths (the second note sits on the last sixteenth of a sixteenth note triplets grid): Hard swing feel.

As far as sixteenth note swing feel goes:

- Straight sixteenths: Straight feel.

- In between sixteenths: Feeling ‘in between’.

- Sixteenths perfectly on the triplet: Perfect shuffle/swing feel.

- Narrow sixteenths (the second note sits on the last thirty-second of a thirty-second note grid): Narrow swing feel.

- Hard sixteenths (the second note sits on the last thirty-second of a thirty-second note triplets grid): Hard swing feel.

Using different levels of swing is nothing new. Back in the ‘60s and ‘70s drummers like Zigaboo Modeliste, Clyde Stubblefield and Jabo Starks played everything with an ‘in between’ shuffle feel.

In Rock the great John Bonham played often ‘in the cracks’, just a bit swung yet never quite on the triplet.

In Jazz many post-bop drummers were going beyond the triplet based shuffle feel and experimenting with playing more in between (Elvin Jones) or more towards a dotted eighth feel (Tony Williams).

Today drummers like Steve Jordan use them all the time.

The studies included in the PDF cover the 5 swing levels explained, both in eighths and sixteenths, and both on the Snare and in rhythmic examples.

The ‘in between’ swing level is played very loose and without a specific underlying subdivision, since I think it sounds more musical this way.

If you want to practice this version using a quintuplet grid (as mentioned before) you can check out the article ‘Quintuplets – Drum Grooves – Fills – Practice Loops‘ which includes additional free videos and transcriptions.

We’ll wrap it up with 8 sample beats to practice: 2 for each level, straight version excluded.

You can click on each example in the PDF to access the related demonstration, or watch the full 11 minute YouTube video by clicking HERE.

Below are a few examples from records, which we can check out to get a taste of the way each solution sounds, and also practice playing along to, in order to internalize the feel involved in each level:

- In between eighths: Save Your Love For Me (Jose James).

- In between sixteenths: Free Your Dreams (Chantae Cann).

- Eighths perfectly on the triplet: Uprising (Muse).

- Sixteenths perfectly on the triplet: Sunday Morning (Maroon 5).

- Narrow: What They Do (The Roots).

- Hard: The Root (D’Angelo).

As a bonus exercise, we can try listening to music and paying attention to the level of swing, when present, to try to figure out the amount used.

Mastering these concepts is going to make a huge difference in the depth of our groove and the nuances in our timing.

Related resources:

‘Groove Mastery & Formulas’ – Altitude Drumming – Volume 8

‘Theory & Concepts’ – Altitude Drumming – Volume 1